The War on Vulnerabilities

There is a growing trend in cybersecurity to hate on vulnerability reports, pentests, bug bounty, and security research. We’ve entered an era where AI-driven LLM slop accelerates this process. It’s simply easier to discount “vulnerabilities”.

Companies are swamped by CVEs and low quality “beg-bounty” reports. It’s fair to say that it’s difficult for vulnerability management and application security teams to stay on top of all of the information.

Adding insult to injury, inexperienced people are often laughed off for reporting missing security best practices.

What Actually is a Vulnerability?

This term ends up being a large catch-all and often interpreted incorrectly. Wikipedia’s definition is fairly good:

A vulnerability is a flaw or weaknesses in a system’s design, implementation, or management that can be exploited by a malicious actor to compromise its security.1

Many issues arise from being overly generous or narrow with this definition.

An overly broad claim may be that everything is a vulnerability. An attacker could possibly benefit from a weakness, regardless of direct or indirect exploitability (I benefit from ABC, but in order to use this information/weakness I need XYZ).

A narrow definition may claim that vulnerabilities need to be exploitable to be valid.

In the overly broad case, there has to be an acceptable level of risk. Is it a vulnerability for a company to simply have a web server exposed to the internet? By definition, yes, it might be able to be exploited and therefore have some risk associated with simply being exposed. The outstanding question should be: Is that a vulnerability that should be reported?

In the narrow case, this leads to a naive approach that no one is capable of using the issue to their benefit. Are you certain that this bug couldn’t be exploited by an attacker with infinite resources (time, money, people, etc)?

Understandably, these lead to some frustrations when someone claims something is a vulnerability and another party disagrees.

Exploits

Similarly, let’s take the definition for an exploit:

An exploit is a method or piece of code that takes advantage of vulnerabilities in software, applications, networks, operating systems, or hardware, typically for malicious purposes.2

This means that an exploit can be a technique or usage of a known vulnerability. An exploit requires action, rather than something that can be passively observed.

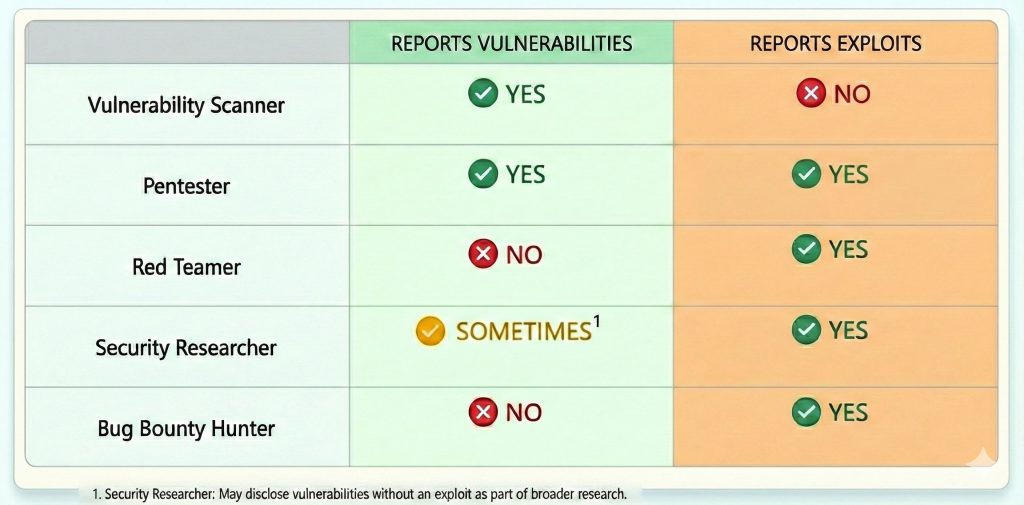

Who Reports What?

What Needs to Change?

The information security community needs to correct our language.

- Bug Bounty platforms typically only accept exploits, not vulnerabilities. Platforms/programs need to be explicit about what is accepted.

- It’s perfectly okay for some companies to accept vulnerability reports and for others to require proof of exploitation. Companies need to use clear language in their security policies (Ex: security.txt).

- Different scoring mechanisms than CVSS are needed for unexploited weaknesses. Fudging CVSS vectors through broad interpretations undermines trust and authority.

If our community can’t correctly explain the difference between vulnerabilities and exploits, then what hope do developers and other tech-related positions have trying to understand what is reported?

Additionally, instead of aggressively blocking offensive security tooling by LLMs, work needs to be done to help teach LLMs about vulnerabilities and exploits. This will reduce AI-slop on the bug bounty side. Companies should be using AI to help cut through the noise and prioritize issues according to their goals.

Example Security Policies

A brief example of a security policy for a company wishing to only receive exploits:

Company ABC is focused on accepting exploit reports. Ensure that a working proof of concept is provided and an explanation regarding what direct harm the exploit allows for. Please include any limitations that an attacker would need to take into consideration. We do not accept missing security best practices unless they are used as part of an exploit.

Compared against a company that is okay accepting either type of security report:

Company XYZ accepts vulnerability and exploit reports. We value insights from the security community and understand that exploitation can sometimes be tricky. It’s up to our discretion how we prioritize and reward vulnerabilities and exploits. Please share any applicable details and steps to reproduce. Our security team will assist with determining the overall security impact.

Why Care About Vulnerabilities?

Vulnerabilities without a demonstrated exploit are still vulnerabilities. Every person, project, organization, enterprise, etc. can establish what type of security issues they do and do not care about.

Many organizations care deeply about defense in depth. These companies and people understand that weaknesses can compound the severity of an exploit, so it’s often worth hardening their systems instead of waiting for an exploit.

Being unaware of a vulnerability is ultimately worse than risk acceptance/deference. Negligence is worse than missing accountability.

Closing Thoughts

Offensive security needs to be on the same page regarding who reports what and why. Undermining adjacent roles hurts our community’s credibility.

Not every vulnerability needs to be fixed. I have seen small bugs that would cost millions to fix due to poor architecture decisions. Compliance and auditors need to have appropriate levels of grace.

To Pentesters: Work to find or create an industry common scoring mechanism for unexploited weaknesses. Reserve CVSS for exploits.

To Bug Bounty Hunters: Help vocalize to inexperienced folk the difference between vulnerabilities and exploits. Share that “XYZ would be appropriate to report on a pentest but not on most bug bounty programs.”

Personal opinion: Bug Bounty platforms try to bridge the gap between pentesting and bug bounty with Pentesting-as-a-Service (PTaaS). Most bug bounty hunters (who perform the PTaaS testing) will typically not report passive vulnerabilities or bugs they didn’t exploit, so it’s highly variable to consider the results equivalent to a pentest. On the flip side, many web pentesters don’t practice exploiting issues in-depth and as a result often struggle on bug bounty platforms. Consider the background of “who” is performing assessments and ensure their methodology and results align with your organization’s goals.